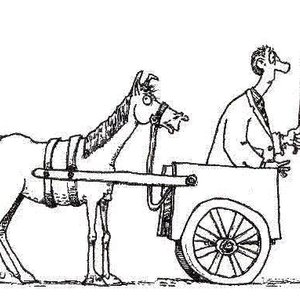

Cart before the horse advertising

Vitamin trials show that medicines should be tested before they are promoted

Published: Oct. 27, 2011, 11:06 a.m., Last updated: Oct. 27, 2011, 11:20 a.m.

Several vitamin trials have been published over the last few years that debunk the claims of many vitamin selling companies. These trials show why it is important to test claims about products before advertising them.

The idea that vitamin E and/or selenium supplementation may reduce the risk of developing prostate cancer used to be a compelling one. Between some lab results and theories of how the compounds may reduce risk, the signs were good. Fortunately for us, a group of researchers decided to test the hypothesis in a large double-blinded, randomised controlled trial.

New results from this trial (known as SELECT: Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial) were just reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association. Roughly 35,000 men had been assigned to get vitamin E, selenium, both, or a placebo. These men were followed for seven or more years. The researchers concluded: “Dietary supplementation with vitamin E significantly increased the risk of prostate cancer among healthy men”.

You may have seen headlines like "Vitamin E Supplements Boost Prostate Cancer Risk, Study Says" and "More bad supplement news: Vitamin E might be risky for prostate" in the last week or so. In fact, the 17% increase in risk is not quite as bad as it sounds. The absolute increase in risk, though clinically significant, was small: only 1.6 per 1,000 person years.

The fact that the lack of risk reduction with either selenium or vitamin E, or both combined, was confirmed in this new analysis is much more important than the small increase in risk. It shows that, no matter how compelling the theory of how a specific compound will fight disease in the body, you don’t really know whether a treatment works until you test it in humans.

This was borne out by Dr Eric Klein (lead researcher on the trial) who told a reporter from NBC, "I was surprised by the results of this trial. . . There was a substantial amount of evidence going into SELECT when it was designed in the early 2000s to suggest that vitamin E or selenium might prevent prostate cancer and that's why we did the trial."

Possibly even worse news for those selling selenium supplements came in a recent Cochrane Review that concluded, "Currently, there is no convincing evidence that individuals, particularly those who are adequately nourished, will benefit from selenium supplementation with regard to their cancer risk."

The vitamin E and selenium cases in some ways mirrors what we’ve seen with antioxidants more broadly. Often touted as miracle cancer-fighters, complete with a wonderfully simple story of how they mop up free radicals, the antioxidant cart has also been put before the horse. Indeed, when compared to the hype, antioxidant supplements have performed dismally in properly conducted trials in humans.

Possibly the best example of this is a Cochrane Review that concluded:

We found no evidence to support antioxidant supplements for primary or secondary prevention. Vitamin A, beta-carotene, and vitamin E may increase mortality. Future randomised trials could evaluate the potential effects of vitamin C and selenium for primary and secondary prevention. Such trials should be closely monitored for potential harmful effects. Antioxidant supplements need to be considered medicinal products and should undergo sufficient evaluation before marketing.

However compelling the test tube, animal, and early human findings may be, it is clear we only really know whether something works once we’ve had proper randomised clinical trials, preferably double-blinded. Yet, when it comes to supplementation, much of what we read on product lables, in advertisements and in popular magazines come precisely from that twilight zone of uncertainty prior to such trials. In other words, in many of these cases we just don’t know yet if a specific product will really make a difference in humans.

Here is an example. Curcumin is a chemical found in the spice tumeric. A local supplement company who sells a curcumin supplement claims, "Curcumin helps prevent the development, and inhibits the further growth of some forms of cancer. Numerous studies have shown curcumin to be beneficial in causing the death of cancer cells by starving the cells of blood supply and oxygen. Research shows that curcumin protects the lungs from damage caused by cigarette smoke."

Now, a search on PubMed does throw up a number of potentially exciting pre-clinical findings and curcumin does seem to warrant more research. However, curcumin has hardly been studied in humans yet – and we have not had double-blinded randomised controlled trials that tell us if curcumin is effective.

You might say that we are now with curcumin for cancer roughly where we were in the early 2000s with vitamin E and selenium for prostate cancer. That is to say that we just don’t know yet. Incidentally, between all the positive studies there was one that found that curcumin impacted on iron metabolism in rats leading to iron deficiency. We shouldn’t read too much into this finding either, but it is a reminder of the fact that much remains unknown and all might not work out as we want it to.

Sadly, the curcumin example is not unusual. Browsing around online and paging through magazines, it seems almost standard practice to market products without any clear evidence of benefit in humans at all. Hopefully new regulations for the registration of complementary medicines will bring an end to this kind of thing, but we will have to see.

Either way, if there is anything to learn from last week’s vitamin E and selenium findings, it is that most supplement advertising should be viewed sceptically. It may sound like science and it may be based (often very loosely) on well-conducted research, but that research is rarely of any direct relevance to consumers. Only when a large randomised controlled trial like SELECT comes along does the picture clear up enough for us to say with any reliability whether or not this or that pill is any good.

Comments in chronological order (2 comments)

Roy wrote on 2 November 2011 at 7:42 a.m.:

Travel Guide wrote on 7 November 2011 at 6:27 a.m.:

Hi, was just going through the google looking for good info and stumbled across your website. I am stunned at the design that you’ve on this site. It shows how you appreciate this subject.

My blog is about [HTML_REMOVED]Travel Guide[HTML_REMOVED].

This is such an excellent overview, Marcus. Thank you.

I particularly like this sentence: "Browsing around online and paging through magazines, it seems almost standard practice to market products without any clear evidence of benefit in humans at all."

You've hit the nail on the head! This is exactly why snake oil sales(persons) are known as quacks. And we have an oversupply of quacks at the moment.